Incidence of Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is a disease that should not be underestimated. Prior to the introduction of Pap smear screening, cervical cancer was the most common gynaecological cancer in women and caused many deaths. This is still the case in underdeveloped countries.

The introduction of a coordinated Pap smear screening program in 1991 has had a dramatic affect on this disease, having produced a decrease in both the incidence and death rate for cervical cancer of about 33 per cent. At present each year it prevents about 1,200 women developing cervical cancer and has resulted in Australia having the second lowest incidence of cervical cancer in the world.

In Australia at present about 800 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed each year and in 2003 about 238 cervical cancer deaths occurred. The vast majority (85 per cent) of these occurred in women who had not had a Pap smear or who had inadequate smears in the last ten years.

Having a Pap smear every two years can prevent up to 90 per cent of cervical cancers and women who have been sexually active at any time (including homosexual women) should have second yearly smears. (Women with a history of abnormal smears will need to have them done more frequently.)

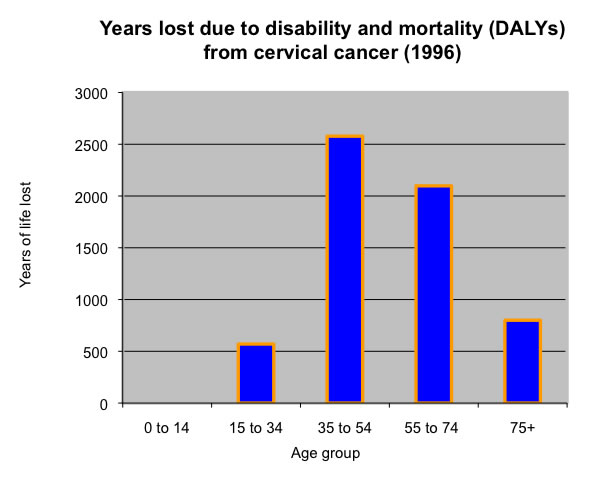

Source – Adapted from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Mathers 1999. |

At present, only about 60 per cent of women have second yearly Pap smears and about 80 per cent have them every three years. This less than optimal Pap smear rate explains why cervical cancer still causes about 2.4 per cent of cancer deaths (335 per year) and the tragedy is that these deaths often occur in young women (see the figure below). Fifty per cent occur before the age of 50.

Having said this, death from cervical caner is still most common in older women and this is partly because the Pap smear participation rate is lowest in older women, especially in the 60 to 70 year age group. Older women who have not had a recent smear need to realise that they are significantly increasing their risk of developing cervical cancer.

The Pap smear participation rate is also lower in low socio-economic groups, in non-English speaking women, and in country areas. This problem is especially prevalent in remote indigenous communities, where lack of screening for cervical cancer has meant that it is the most common cause of gynaecological cancer death. In non-aboriginal Australians the death rate per year from cervical cancer from 1998 to 2001 was is 2.5 in 100,000. In Indigenous Australian women the rate is over five times that of non-Indigenous Australian women (12 per 100,000).

(Back to top)

What causes cancer of the cervix (cervical cancer)?

There are two types of cervical cancer.

Squamous cell cancer of the cervix

The most common type of cervical cancer is squamous cell carcinoma (85 per cent) and almost all of these cervical cancers occur following an infection of the cervix by the sexually transmitted human papilloma virus (HPV). (This is the virus that causes genital warts in both men and women.) Squamous cell cervical cancers are rare in women that have not had sexual intercourse. The sexual transmission of HPV explains why squamous cell cervical cancers are more common in women who:

- have multiple sexual partners

- commence sexual intercourse at a young age

- (Smokers also have an increased risk.)

Luckily, doctors are able to diagnose (and successfully treat) most of these lesions before they become cancerous because it usually takes a long time (about 10 years) for early pre-cancerous changes to develop into actual cancer and these early pre-cancerous changes in the cervix are readily picked up by Pap smears

The natural history of HPV infections - Most HPV infections of the cervix resolve by themselves

In all there are about 40 different types of HPV that affect the cervix, but only about 15 of these are higher risk types that can cause cervical cancer. The most commonly involved types are 16 and 18, which together cause about 70 per cent of cervical cancer both here and overseas. Most women have no idea they have the disease unless they have obvious genital warts or an abnormal Pap smear. In men warts are more easily seen but not all men with a HPV infection will have visible penile warts.

About 80 per cent of women (and men) develop an HPV infection within a few years of commencing sexual activity. The majority of these infections resolve by themselves irrespective of whether the initial infection is due to a high-risk or low-risk type of HPV, with the average time for resolution to occur being about eight months. (This is why repeating an initial mildly abnormal Pap smear should be delayed for up to 12 months; otherwise the repeat smear will just pick up a resolving infection.) By themselves, these initial infections cause only a mild abnormality on the Pap smear and, like the HPV infection that causes them, these mild Pap smear abnormalities usually go without treatment and do not progress to cancer. Thus, in a woman less than 30, it is extremely likely that a low grade Pap smear abnormality is just an indication that the woman has recently contracted a cervical HPV infection. It is not an indication that an early cancer exists.

By the age of 30 to 35, only about 5 per cent of women will have a current infection. This is partly because most women have been previously exposed to common HPV infections that they have subsequently eradicated. In doing this they have developed an immunity to these types of HPV which prevents them becoming infected with them again. (Immunity to one type of HPV does not give immunity against all other types, although it may do to some.) Another factor is that many women in this age group have entered long term (monogamous) relationships and women in such relationships are much less likely to be exposed to a new HVP infection. Thus abnormal Pap smears are less common in women over 30 and, while an abnormal smear in this age group is still unlikely to indicate that a cancer may develop, there is a greater chance that it will represent a lingering infection rather than a new one. Thus, abnormal smears in this age group need to be taken more seriously, especially if the abnormality persists.

Overall, about 0.1 per cent of women with an HPV infection go on to develop cervical cancer. The development of cervical cancer requires a high-risk type of virus to alter the genes of a cervical cell in a way that promotes abnormal cell growth and replication, probably by the incorporation of some of the virus’s genetic material into the DNA of its ‘host’ cervical cell. For this to occur, it is thought that an additional cancer-causing factor must also be present, such as cigarette smoking or the presence of impaired immunity.

Women who are exposed to a strain of HPV and clear this infection gain a lifelong immunity to this strain of HPV. However, infection with other strains can occur.

Prevention of HPV infections

While the use of condoms is vital in minimising the risk of contracting many important sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV and syphilis, they are of little use in preventing the spread of HPV infections as the virus is transmitted by genital skin-to-skin contact. As stated before, 80 per cent of the population develop the disease; it is the ‘common cold’ of sexually transmitted diseases.

Adenocarcinomas (glandular cancers)

The second type of cervical cancer is adenocarcinoma. It arises from glandular cells that make vaginal mucous and these cell lie mostly in the cervical canal. Pap smears attempt to sample cervical canal tissue but it is a more difficult process, especially gaining tissue from higher in the canal where adenocarcinomas more commonly arise. (It is not uncommon for such tissue to be absent from the sampled material.) This relative inaccessibility means that cervical adenocarinomas more difficult for Pap smears to detect and also means they are more difficult for doctors investigating abnormal smears to view. For this reason, the Pap smear prevention program has had very little effect on the incidence of cervical adenocarcinoma, which has hardly changed. They are probably not caused by a HPV infection and thus are not thought to be sexually transmitted. Luckily they are far less common, accounting for only 15 per cent of cervical cancers.

What are Pap smears?

A Pap smear test is the examination of cells scraped off the surface of the cervix using a wooden or plastic spatula and/or a small brush. This tissue is taken randomly as it is usually not possible the doctor performing the procedure to visually detect abnormal tissue. The specimen should contain cells from the surface of the cervix and the cervical canal that leads up into the uterus.

These cells are placed on a glass slide and then examined under a microscope to see if any have abnormalities. These abnormalities can vary in severity from a mildly atypical appearance to actual cancer. While in some women taking a Pap smear can be slightly uncomfortable, it is not usually painful. (Women can discuss the actual procedure with their doctor.)

In pre-menopausal women, the best time to collect a specimen is probably mid-way between menstrual periods, although getting a good quality sample of cervical cells is far more important than when in the menstrual cycle the smear is taken. Contact bleeding with the procedure is relatively common and does not increase the likelihood that cancer is present. It is best to avoid having a smear when an infection such as ‘thrush’ is present. Also, the use of douches and vaginal creams should be avoided in the two days prior to having a smear.

The vast majority of male GPs, while being extremely competent at performing Pap Smears, understand that some women prefer a female doctor to perform the procedure and are very happy for them to choose this option.

Veda-Scope smears |

(Back to top)

Who should have Pap smears?

Pap smears done as advised by health authorities reduce rates of squamous cell cervical cancer by up to 90 per cent and therefore are recommended for all women who have been sexually active. They should commence at the age of 18 or within 24 months of first sexual intercourse, which ever comes later. (About 35 per cent of women show evidence of HPV infection within two years of becoming sexually active.) It is considered safe for women to stop having pap smears at age 70 if they have had two normal smears in the past five years and have no symptoms.

A woman who has had a total hysterectomy does not need pap smears when allthe following apply;

- there was no evidence of uterine or cervical cancer found at the hysterectomy

- all previous smears were normal

- she is not severely immunosuppressed

- she has had no symptoms.

Otherwise, Pap smears may still be necessary. (Women should discuss the need for a Pap smear with their doctor.)

Pap smears are a screening test

Routine Pap smears are a screening test. This means that they are used to assess women who do not have symptoms that might suggest cervical cancer. These symptoms include abnormal vaginal bleeding and pain with sexual intercourse. It is important for women with such symptoms to have them investigated when they occur. A negative last Pap smear does not mean that cervical cancer cannot occur and it is not appropriate to wait till the next smear to investigate the cause of the symptoms.

Monitoring Pap smear programs

To help increase compliance with this optimum Pap smear regimen, there are now national and state programs to monitor women participating in Pap smear screening. They incorporate promotional schemes, registries and recall systems for women who have had previous smears.

Older women still need smears

As stated previously, the Pap smear participation rate is lowest in older women and unfortunately this is the age group in which most cervical cancer occurs. A history of previously normal smears does not mean that the woman can safely stop having Pap smears and older women who choose not to have smears regularly put themselves at significantly increased risk of cervical cancer

Newer methods of examining cervical cells taken during Pap smears

Over the past few years, newer laboratory techniques aimed at more accurate diagnosis of cervical cancer have been developed. These tests are done in addition to the normal Pap smear test (i.e. the specimen is examined twice) and are paid for by the patient.

1. Different slide preparation (ThinPrep / Autocyte tests)

With this method, a conventional slide for the routine Pap smear is made and the remaining cells are placed in a liquid medium. The slide subsequently prepared from this liquid medium enables the pathologist to have a clear view of just the cervical cells. This is a slight advantage over normal smears as normal smears are sometimes difficult to read due the presence of thick mucous or blood. Problems with reading conventional smears mean that about one to two per cent of conventional smears need to be repeated and the use of these types of smears may be useful in reducing this incidence in women with previous ‘inadequate’ smears or in women who have excessive mucous, blood or discharge present when the smear is being taken that may make a conventional smear difficult to read. While there is some argument at present as to whether this is benefit significant, a back-up slide may prevent the woman needing to return for a repeat test. The extra cost is about $40. The choice is often left up to the patient.

With regard to cervical cancer detection, there is no convincing evidence that these newer techniques are better at detecting high-grade lesions. They do detect a few more low-grade lesions but most of these will resolve without the need for treatment.

At present these tests are read manually and a newer test that uses computer reading will probably be available in Australia next year. Whether it has more definite advantages time will tell.

Please remember: Eighty-five per cent of cervical cancers in Australia occur in women who do not have regular second-yearly smears.

2. Retesting conventional smears by computer (PAPNET and Autopap tests)

These techniques use computer-assisted microscopes to look for abnormal cells and they have been shown to pick up a few more abnormalities. Due to their expense, these tests are mostly used for laboratory quality control. That is, they are generally not available to women having Pap smears

Chlamydia testing with Pap smearsChlamydia is a common infection in young women, especially those who have multiple sexual partners, and it can cause fertility problems later in life. Pap smear testing time is also a good time to have a screening test for chlamydia in those at increased risk of the disease. See pp ?? for more information. |

What does a normal Pap smear mean?

Pap smears are not perfect. Abnormalities can be missed and this is one of the reasons why Pap Smears need to be done every two years. (Overall, about 10 per cent of abnormal cervical lesions are missed by Pap smears, the rate being higher in women under 40 years of age. Luckily most will either be picked up at the next smear or be mild abnormalities and go away naturally.)

A normal Pap smear means that the woman has a very low risk of either having cancer or developing cancer in the next few years. It does not indicate that the woman has no risk of developing cancer. Women with symptoms such as bleeding or pain with sexual intercourse or bleeding between periods or after menopause cannot assume that they have no cause for concern because their last Pap smear was normal. They should consult their general practitioner to make sure there is no serious cause.

Pap smears occasionally need to be repeated due to difficulty in interpreting the cells taken. This occurs in about two per cent of smears and is usually due to too few cells being present, the presence of blood and mucous making the cells difficult to see properly, or the cells being slightly inflamed for some other reason. If a Pap smear does need to be repeated, it is best to wait about two to three months to allow the cervix to ‘grow back’ to normal.

What does an abnormal Pap smear mean?

Pap smears are not just normal or abnormal. There is a range of ‘abnormality’, varying from mild changes to actual cancer. Abnormal smears are divided into two main groups; low-grade and high-grade lesions. Each year about two million Australian women have a Pap smear and about 100,000 of these smears will reveal a low grade abnormality and about 20,000 will reveal a high grade abnormality. These two abnormal groups require quite different management as discussed below.

For women who choose to have regular second-yearly Pap smears, the chance of having an abnormal smear at some time is about 40 per cent. Obviously most of these abnormalities will be low grade and clear without the need for treatment.

Low-grade abnormalities

Previously low grade abnormalities have been divided into several sub-groups according to their perceived severity. (These included atypia, non-specific minor changes, HPV changes and mild dysplasia or CIN1.) As well as being a confusing classification, actually making such differentiations pathologically is not easy and this led to inconsistencies in the interpretation of Pap smears with low-grade abnormalities. It has also been shown that the prognosis of all the different types of low-grade lesions is very similar, with the vast majority being short-term changes due to a transient HPV cervical infection that will resolve without any treatment, leaving a normal cervix. (In the past, such lesions were all viewed as pre-cancerous, leading to unnecessary worry.)

Thus, for the purposes of deciding on what further investigation a low-grade abnormality requires, it has been decided to group all low-grade abnormalities together and they are now all termed low-grade squamous epithelial lesions. The management of such low grade lesions is summarised in Figure ?

There are four classifications of low-grade lesions; termed low-grade squamous epithelial lesions;

- Atypia – minor changes in the appearance of the cervical cells.

- Non-specific minor changes – usually indicates that either there is infection, inflammation or irritation present that has affected the appearance of the cells.

- Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) associated changes – indicates HPV is present. For the majority of women this virus will usually clear up on its own. (It is necessary to increase the frequency of Pap smear testing until the virus has cleared up.) In cases where the changes persist over time further investigations by a gynaecologist may be necessary.

- Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia grade 1 (CIN 1) / Mild dysplasia – this describes the presence of very mild abnormal changes in the cervical cells. Depending on its severity, women with this lesion may either be followed-up with more frequent Pap tests or may be referred for definitive treatment. For 60% of women this abnormality will resolve spontaneously without treatment. For the remaining 40% of women, where the abnormality is persistent or progresses to a higher-grade lesion, further investigation and treatment by a gynaecologist is required.

B. High-grade abnormalities

This group of conditions is divided into three groups as follows. (It includes the old CIN 2 and CIN 3 classifications.) All these lesions require further investigation with colposcopy.

- Possible high grade squamous epithelial lesions

- High grade squamous epithelial lesions

- Cervical cancer – A Pap smear that identifies a cervical cancer requires immediate follow up by a gynaecologist, preferably one who specialises in cervical cancer if available.

All high-grade lesions require further investigation and treatment by a gynaecologist. The majority of high-grade lesions develop into cancer. This progression is usually (but not always) slow; it often takes eight to ten years. Thus, proper treatment of these abnormalities should prevent the future development of cervical cancer in most cases. However, Par smears are not as accurate as colposcopy and a few women with high-grade lesions may actually have cancer. Thus, the initial investigation by colposcopy of all high-grade lesions should not be delayed.

Women who have had a high-grade abnormality need yearly smears

About a quarter of million women in Australia have had a high grade Pap smear abnormality at some time in the past. These women are at higher risk of developing cervical cancer and require different prevention programs. In the past this has been to have yearly smears for the rest of their lives, although there are other options now recommended and the woman needs to discuss these with her gynaecologist.

All changes in glandular cells need investigation irrespective of whether they are low or high grade

As stated above, changes occurring in glandular cells (which may lead to adenocarcinoma of the cervix) are more difficult to identify by Pap smear and more difficult to treat. It is therefore important to have a high level of suspicion when dealing with abnormalities in this type of cell and all Pap smears that show changes in glandular cells need further investigation by a gynaecologist.

Colposcopy |

Abnormal lesions are investigated by a gynaecologist using colposcopy. This involves the use of an instrument (a colposcope) to magnify the appearance of the cervix in order to help determine where the abnormal cells are coming from. The area is identified by applying some iodine to the cervix with the area of cell change remaining pale. A biopsy (sample of tissue) is taken from the pale area during this procedure. |

Women who have had a high grade abnormality need yearly smears.

(Back to top)

Living with a mild abnormality

In the past, due to a lack of understanding about cervical cancer, it was normal to investigate all abnormal smears. This approach led to unnecessary investigations and treatments which in turn meant some women suffered an increase in illness because:

- all investigations and treatments are associated with the risk of side effects or occasional adverse outcomes.

- the implication that they had a ‘pre-cancerous’ lesion increased anxiety in many women; and anxiety is already a major illness for women of all age groups.

It also led to increased financial costs to the community; and thus reduced funds for other government expenditure, such as education.

Recognition of the above has lead to doctors being asked to treat most mildly abnormal smears by waiting and seeing what happens. Adopting this management regimen also means that;

- many women are going to be asked to live for a short period (up to 12 months) with low-grade abnormality that may, al-be-it rarely, turn into a cancer. This may unsettle some women and they will need to discuss this issue with their doctor.

- there may be a very, very small increase in the number of cancers that will be missed.

However, the alternative is to continue treating mild viral infections of the cervix as if they are cancer and, as a group, women who do this will probably be worse off.

More information about cancer and its evolution can be found in the section on Preventing Cancer.

Screening techniques for detecting Human Papilloma Virus

As stated previously, there are about 35 types of HPV that affect the cervix with only a few high-risk types being responsible for cervical cancer.

In women over 35, there is a strong association between persistent HPV infection (over six months) and high-grade cervical abnormalities. In these cases, testing for HPV may be of benefit in predicting those likely to develop cancer. At present, this test is not recommended as a screening test by the National Health and Medical Research Council because the test can not tell which HPV infections are likely to cause cancer and there is a high incidence of positive tests for HPV that are not causing cancerous lesions.

Also, testing should not be done in women under the age of 35 as the false positive rate is far too high in this group. This is because women under 35 yrs have a much higher incidence of recent HPV infection and a positive test for HPV in this group is usually indicating an acute infection that will resolve by itself without causing any harm.

The test for HPV can be done when performing a Pap smear (by taking a swab cervical swab or on fluid from a ThinPrep or Autocyte test.) The test is relatively expensive and all paid for by the patient.

(Back to top)

Vaccination against Human Papilloma Virus

Vaccines are now available that will prevent women becoming infected with the two main types of HPV that cause cervical cancer; types 16 and 18. These two viruses are responsible for about 70 per cent of cervical cancer. Unfortunately the vaccine will probably not help prevent the 30 per cent of cervical cancer that is caused by other cancer-causing types of HPV and this means that, to adequately prevent cervical cancer, women will need to continue to have Pap smears irrespective of whether they have had the vaccination or not.

Significantly, as well as preventing cervical cancer, the vaccine will also reduce (by roughly 50%) the incidence of abnormal high grade abnormality Pap smears and thus the need for their investigation and treatment and the anxiety such diagnoses cause. (In Australia in 2004, 14,500 women were diagnosed with high grade lesions.) The vaccine is administered as three injections over 6 months.

The vaccines are made up of virus-like particles, which are not infectious. (As the vaccines are not a live attenuated viruses there is recommended interval between administration and becoming pregnant. However, they should not be given while a woman is pregnant.) The vaccine is well tolerated, with the main problem being slight swelling and redness at the injection site.

At present it is thought the vaccines will last about 10 years and that at least one booster will be needed. However, it is early days regarding the vaccine and this may prove not to be necessary. There are two vaccines presently available.

- Gardasil: This vaccine provides protection against the two main cancer causing types of HPV, types 16 and 18, and the types 6 and 11 that cause over 90 per cent of venereal warts in females and males. These can be unsightly and painful, and difficult to treat. This vaccine is subsidise by government for use on females aged 12 to 26 years. It is not subsidised for use on older females or males. There are three doses given at 0, 2 and 6 months. (This an be compressed to 0, 1 and 4 months when required.)

- Cervarix: This vaccine only provides protection against the two main cancer causing types of HPV, types 16 and 18. (This vaccine has received approval for use in women from age 10 to 45 years. However, as of April 2008, this vaccine does not receive a government subsidy. There are three doses given at 0, 1 and 6 months.

Both vaccines will also provide some protection against other cancers that are caused by HPV, namely 70% of anal cancers, 20% of oropharyngeal cancers and 50% of penile cancers (when the vaccine is administered to males).

Target age group for the vaccine

The vaccines will give the best chance of protection if given before a woman becomes sexually active and optimally should be administered by the age of 12.

At present, the group being specifically targeted for vaccine administration is 12 to 26 year old females. The vaccines may also help protect older women, but this benefit is less likely. It is thought that the number who would benefit would benefit in the over 25 age group would be between 20 and 50 per cent. This compares with about 70 per cent in women who are vaccinated prior to commencing sexual intercourse. The reasons for this reduced likelihood of benefit are that many women in this age group:

- will have already contracted the virus from previous sexual intercourse. (Women who have previously contracted a strain of HPV that is associated with causing cervical cancer are unlikely to benefit from the vaccine. The likelihood of this having happened is related to the number of sexual partners the woman has had.)

- are in long term relationships and therefore are less likely to contract a type of HPV virus that they have not previously been exposed to.

Women over 25 years of age who have previously had limited sexual contacts or who are not in a long term relationship (or who are leaving a long term relationship) are more likely to gain protection from contracting HPV by having the vaccination. Women interested in having the vaccine are best to discuss this issue with their GP. There is very little likelihood of harm in having the vaccination but it is expensive.

The vaccine is safe with very few side effects. The most common is some soreness around the vaccination site and very occasionally allergic reactions occur.

All vaccinated women need to continue to have Pap smears

It is important to remember that the vaccine does not give any woman 100 per cent protection from cervical cancer and that Pap smears still need to be done second yearly in any woman who has had sexual intercourse. This is especially the case in women who have had sexual intercourse prior to having the vaccine. One worry about women over 25 having the vaccination is that there is a considerable risk that they already were infected with HPV prior to vaccination and thus the vaccine gave them no protection. Should they then decide to have Pap smears less regularly because they think they are well protected, they will put themselves at significantly increased risk of getting cervical cancer.

Giving it to males will also help prevent the spread of HPV infection in the community, although use in males is not subsidised at this stage and the cost is about $440 for the three vaccinations required

Further information

National Cervical Screening Program

http://www.cervicalscreen.health.gov.au/ncsp/